Lapland explorer

“It’s -20ºC outside, and I’m alone. I’ve been out here for

five

days, kiting when the wind shows up, or walking (a lot!) pulling my 70kg sled, making my

way

through the white desert of Lapland. Wounds start to form under Whakatau - my new

reconstructed heel. I am 150km from the closest exit when I realize my fuel canister

leaked.

Without fuel I cannot eat, I cannot drink, and I cannot heat myself.

I am scared.”

Despite what many people think or say, I am not fearless. Deciding to go out on a solo expedition across Lapland when I am still lying in my hospital bed and can barely walk is not being fearless. Rather it is a product of resilience: hard work, dedication, commitment and adaptability.

Let’s take a step back.

I am Nika. I grew up in sunny Barcelona, with wild dreams and no female role models to look up to. As a kid, I felt that being a pioneer in the outdoors or good in science were reserved for men. When I grew up, I stopped dreaming and started creating my own path: I became an engineer, an adventurer, and an entrepreneur.

September 2019, committed to inspire the next generation of girls to dream big, I am ready to embark on what I believe to be the greatest adventure of my life. I plan to face the unpredictable storms from the Mediterranean to become the first person ever to cross from Mallorca to Barcelona on a kitesurf - alone.

The day before departure, life decides otherwise when a motorcycle accident sends me to hospital. The injuries are bad : 15 broken bones, and a dream is torn to shreds in a fraction of a second. It’s the most excruciating pain I’ve ever experienced. During the following weeks, to avoid leg amputation, doctors perform a full reconstruction of my heel. I name my new heel Whakatau after a Maori warrior - it will become my new adventure partner.

The 12 months that follow are a rollercoaster of emotions in the hospital: effort, sweat, friendships, successes, setbacks, and a constant process of adaptation. After several months, my new left foot is still as big as a football, definitely not the most practical for an outdoor-adventure lover. But challenges are thrown at us so we can turn them into opportunities. I decide to launch a new fashion - the summer running shoe! For some reason it hasn’t had too much traction yet…

Winter comes, and on weekends I escape the rehab clinic in my wheelchair to partially

recover my lost freedom in the mountains as I learn how to sit-ski.

Eventually, months go by, and I can go back to mountain-biking, skiing on both of my

feet,

paragliding and kitesurfing.

Being back out there feels good, very good. But I am still missing something. I know there is nowhere I feel more alive than on an expedition - out there, exploring new places by my own means, exposing myself to the unknown… that place where I know I will make mistakes and might not succeed, that I will live in a permanent “problem-solving” mode. Expedition is also where I go back to the most basic survival needs: Move: Eat. Drink. Sleep. Repeat.

I need to feel alive again and prove to myself that I am still “in the game”. My game. I want a challenge that will be not only physical, but also mental and require me to learn new skills.

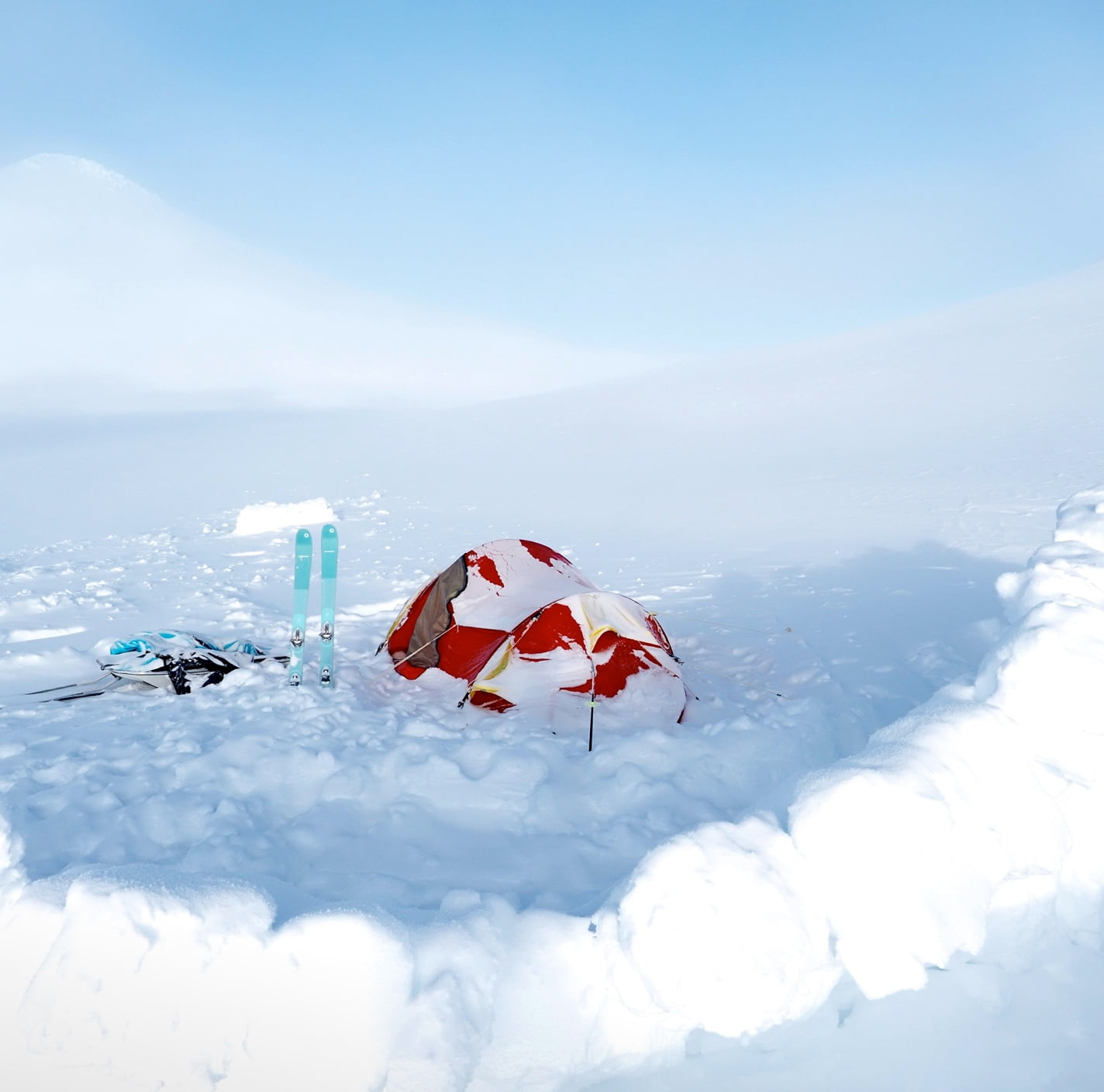

There is something magical about the cold and snow that has always captivated me. Still, from my hospital bed, I look at the map and draw a line across Lapland. Deep above the arctic circle, storms can be brutal, and temperatures can go down to -30ºC. My new challenge takes shape - this is where I am going. And if I go, I go by my own rules: alone and unsupported. Only with my skis, my kites, a sled, and a compass. I have never slept in a tent on the snow before, have never experienced freezing temperatures for an extended period of time, and all I've seen from Lapland are nice postcards of snowy hills…but this is not going to stop me. I have so much to learn.

Gear, frostbite, weather, route planning, safety plan…millions of questions running through my head. I reach out for help: fellow adventurers, Lapland locals, expedition doctors… I am amazed by the support I receive to help me plan my adventure.

After months of planning and training, one main question remains, though - how will Whakatau react to long hours of walking in extreme cold? I won’t know until I try.

April 2022, time has come. A huge storm delays my departure for 2 days. The route I’ve planned has never been done before - locals give me that incredulous look and try to dissuade me. They should’ve known me better. I have many weaknesses but at least one strength:

I owe this to myself. But I mainly owe this to all the girls who grow up without role

models.

And I owe this to all those people whose lives are turned upside down in a matter of

seconds. To give them hope. It will be tough, but they too, will be able to feel alive

again. They are the reason I decided to also take a couple of cameras to try to film

myself and share my story.

On April 7th, I set off from Kilpisjarvi. Mika & Karo, my Finnish guardian angels, tag along on the first morning.

Then… it becomes real. I am alone. I look around, a perfect landscape in shades of white. The snowy hills melt into the white clouds in the white-ish sky. All white. I keep on going. All I hear is my skis sliding on the snow. When the wind kicks in, I kite, when it doesn’t…I walk and pull the 70kg-sled behind me. Any small uphill is a battle in itself.

A huge storm is forecasted for my second night out - I find a small hut to spend the night. The next morning, the snow has blocked the entrance door. I am locked inside. There is a tiny 5cm opening in the door, and the only other way out is to break the small window. I should have stayed in my tent!

A compass-reading mistake makes me land way more south than I had planned to cross the dreaded Reisa canyon at the Norwegian border. As I make my way through the snow is soft. Too soft. I sink down to my waist. I am terrified at the possibility of getting wet in these freezing temperatures.

The sled is heavy, and steep 100 md+ are waiting for me on the other side of the river as soon as I manage to get out of this hole! Even if there was wind, there are too many trees to even attempt to set up the kite. Every step is a tremendous challenge as I try to make my way up. I put one foot in front of the other and pull with all my strength, but the sled keeps pulling me back down. What a battle. I am exhausted.

Wounds start to form under Whakatau when the worst of my fears materializes. My clothes’ duffle bag stinks like fuel. I immediately knew what happened - my fuel canister leaked. I managed to recover around 600ml…from the 3.5L I still had. My guess is that I could still go around 2-3 days on “fuel-saver-mode”. At -20ºC, fuel is essential. Without fuel, there is no eating, no drinking…and no warming up!

I look at the maps again to reconsider my route options. Calling for rescue would feel

like

a failure. Either I walk through the woods and soft snow for 60km, or I am 150km away

from

the nearest exit, in theoretically open kite-able terrain.

I could eventually make it out…if the wind kicks in! There is no way I can walk that

far,

let alone with Whakatau already suffering. The weather forecast is not too promising…

I am scared, I am scared of being cold, scared of not making it out without rescue but mainly scared of letting down those who trusted and supported me.

Will I make it out in one piece...and without rescue?

Kilpisjarvi (Finland) -> Masi (Norway). 11 days. 495km. 4 kites. 2 skis. 1 sled. 1 tent.

A big thank you to Harri Rautava, Louis Marxer, Alex Satori, Mika & Karo Bjorkmann &

Ahti for all your tips and support. And to my support team Sophie, Ben, Leo, Laura, Greg

& Marta.

I could not have done it without you.